Submitted by his mother, Cheryl Finnegan

Who James was

Since childhood, strangers were just friends he hadn’t yet met. James had a gift of connecting to all people. Upon greeting you, James would wrap you in the biggest of bear hugs. Once embraced, you were a part of his family.

His nickname was Lunchbox

He was a bit heavy, and what I heard was that in high school, kids would make fun of him, so he would make self-deprecating jokes. He came up with that nickname, and it stuck.

He was a musician

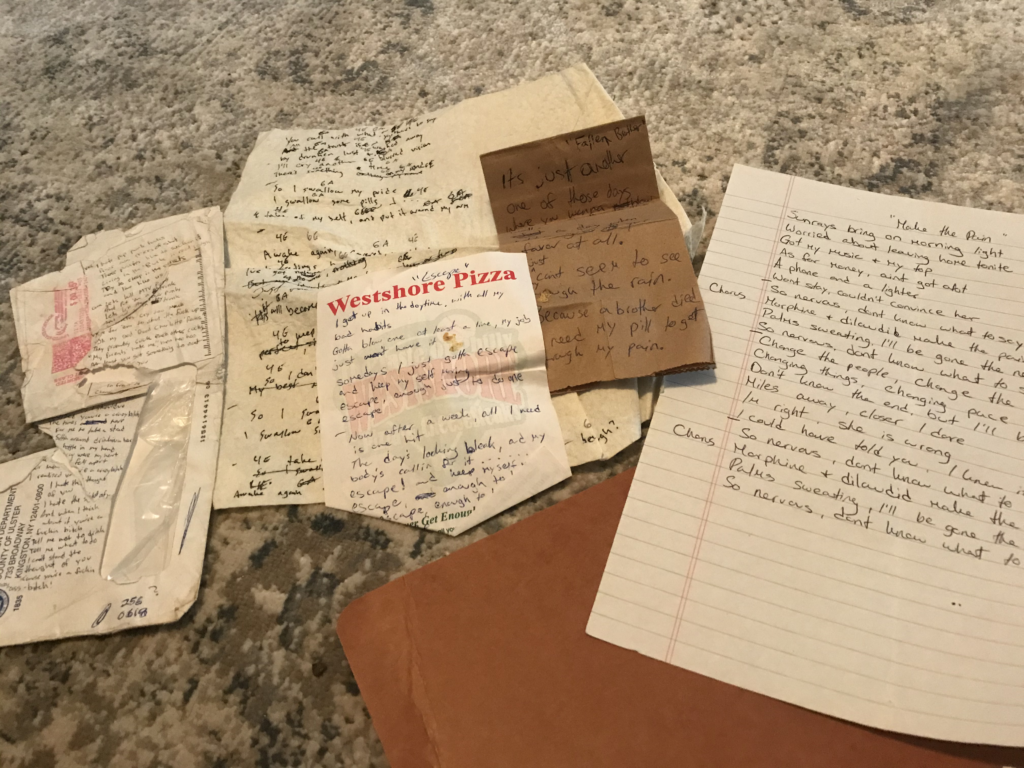

James was a self-taught guitarist and bass player. He was in a punk rock band — Exit 17 — and was the lead singer, as well as songwriter.

He was always writing lyrics. He wrote constantly. He wrote on napkins, envelopes, paper towels! I took him to church one year for Easter, and he was writing a song on the program for the service. It was all very anti-Church and about hypocrisy.

As a mom, I feel horrible now because it wasn’t my kind of music. It was so loud with a lot of yelling. I would always tell him, “You have great lyrics, but I can’t hear them because of all the screaming.” One of my greatest regrets is that I never saw him play live.

How drugs became a part of his life

James began using substances as a young teen. I found out when he began having trouble with the law. He began using pills and, by 20, was injecting heroin.

He had song lyrics about drugs. In the beginning, he was glorifying them. I think he thought it was part of being an artist. But by the end, he was writing about not being able to escape. I think he kind of knew where it was going to take him.

How James fought opioid-use disorder

James struggled for about 10 years. He would get in trouble with the law for petty offenses, and that would send him to jail or rehab. His last foray in the justice system ended with 21 months in recovery. At that point, he was finally being treated for his bipolar disorder. James was also being given suboxone for the first time. Things were looking hopeful for us all. It was one of the longest periods of recovery he experienced, and I’m forever grateful for that time.

How James died

He went through a tough breakup, and he relapsed. And he didn’t want to tell anyone, or get help, because he didn’t want to violate his probation. He didn’t want to go back to jail.

His passing was really strange. I don’t have all the details. He was supposed to perform with his band that night, and he didn’t show up, so someone went over to his house. He had accidentally overdosed, and his friends tried to help him. They ended up bringing him to the hospital.

How I found out

I’ll never forget this. It was eight o’clock on a Sunday night. I was about to sit down and watch the Ken Burns documentary on the Vietnam War. It was one of those moments when I thought, Ah, I’m all caught up at school. (I teach first grade.) I had one daughter who was in college; she was finally settled in. The house is clean. Life is organized!

And then a police officer came up our driveway. My husband, James’ stepfather, is on the local rescue squad, and he knows the police, so he went out there to talk with him. Then my husband ran up the stairs and said, “James is in the hospital. It’s really bad.”

We went over there. He was in the hospital for two days. For the first day, I had hope. But then it became clear he was not going to improve. We just had to keep him alive for James’ father and siblings to come up from New Jersey. We took him off of life support at 9:45 the second night.

I’m grateful we had that time with him. I know people whose kids have died alone or on the street. At least I got to hold his hand. I could feel him squeeze my hand back that first day. I got to watch him take his last breath, which is a weird thing to be grateful for, as a mom.

What I’ve learned since James died

I’ve been in recovery from alcohol for 31 years. James never saw me drink. I got to recovery through Alcoholics Anonymous. Part of what I’ve worked through in the past two years is understanding his struggles were very different than mine. Opioids are a different beast. That one-size-fits-all recovery model just doesn’t work.

James would talk to me about recovery, as if I was his sponsor, but the 12-step tools I was trying to give him weren’t going to fix it. He was bleeding out, and I was offering a wrench.

I’ve done a lot of research to get up to speed on this. Relapsing is very common in achieving recovery from opioids. It’s part of the process of beating this disease. But our system isn’t set up for this. It penalizes people when they relapse.

And there’s still so much stigma and shame. It’s only recently that I’ve been able to talk about recovery — even after 31 years. You should watch the documentary The Anonymous People on YouTube. There are so many of us in recovery who have been quiet, who have held on to that shame. We need to speak out.

How James’ friends reponded to his death

Right after he died, Exit 17 held a tribute show called Box Fest, with his band and others, and they held it again last year. They gave money they raised to a local recovery house, and they distributed Narcan kits. Someone came up to one of James’ friends this year and said he had used the Narcan he had gotten at the last show to revive a friend when he overdosed.

If I could say one thing to James right now, it would be

I truly didn’t understand your struggle. I wish I could have given you more support instead of making you prove yourself. I am so proud of you. I love you, to the moon and back.

So many with box but Luke’s wedding

Was the last time I seen him and luke myself box and sid all look dapper in that photograph box was allways accepting of everyone and could allways get you laughing and had ways of makeing you forget you were sad or angry his heart was gold and that song boby downsyndrom played in his own club PRICELESS

Lunchbox was a truly dynamic individual…..

He looked up to Nikki Sixx, from Motley Crue, and G.G. Allin from G.G.Allin and the Murder Junkies. They were the 2 most prominent influences on him as far as “rockstar behavior”….. I took him down to New Jersey one year, to see his family. I loved his family so much. It was a great time. We had dinner, went to the beach, and had fun. He played music with such pure joy amd enthusiasm…

I remember when we were rehearsing at Randy Crum’s house one night. I had tried multiple times to hit the ending high note in Judas Priest’s, “The Ripper” . After about 2 weeks, one night I finally NAIKED it, and Lunchbox cheered really loud, amd his whole face lit up. I’ll never forget that.

We used to jam in my kitchen. I had a CB drum kit amd he would turn his bass amp all the way up, shaking the whole building. We ignored the banging on the door of pissed off neighbors and just keep playing til the cops showed up. We were drinking then, but no drugs. Those were good times, amd I’ll always co sider him my little brother. He would call me from Florida, amd always said, “What’s up, big brother?”

The world has lost a truly amazing and loving person.

Seeing The misfits at the chance.

Walking the meditation circle at St. Gregory’s in Woodstock

Driving lunchbox in a fully packed out car to a birthday celebration after our bands played a show together in Brooklyn as I was leaving that night we picked up some beers from the deli and he had me try this beer named resin. Ever since then I can’t help but get it when ever I see a bar have it in stock and it’s always a toast to him and what a genuine friend he was even tho he was in new paltz and I was in Staten Island it always felt like no time passed whenever we’d see each other

I work at Snug Harbor and during Lunchbox’s last stint in recovery he would come to the bar at 10 in the morning while I was trying to stock the bar and do inventory. He always had his guitar with him at this point and would stop what ever I was doing to play me he’s latest song that he was working on. I really miss those moments with him. He was stone cold sober and anyone who knows James knows he was super passionate about his music. That’s how I’ll always remember him. Happy birthday buddy. We all miss you very much.

I remember when I moved to new paltz he lived in the same apartment building as I and we were only a door apart. He was so welcoming and sat and he played guitar while I sang. We are both song writers so we would talk lyrics and we both saw that our hearts were trying to tell a story, and would discuss certain pains we had gone through and such. He was so sweet hearted and hysterical. Later we wound up being coworkers and he was so protective and happy and always brought light to a room! I am beyond grateful to have known such a friend as lunchbox || James you forever sing a song no one will forget ❤️ Happy birthday buddy