Submitted by Brennan’s mother, Margery Keasler

What Brennan was like

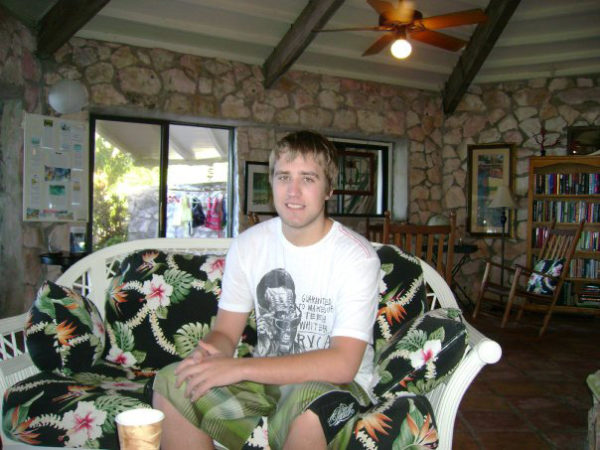

Brennan was beautiful, kind, smart and so funny. He stood 6 foot 3 with blue-green eyes and dirty blond hair. He was an adventurer, a traveler, an amazing snowboarder. He was the oldest of our three kids. Family meant everything to him.

People say that girls are more sensitive, but Brennan was a sensitive kid. He went through a tough breakup before he went to college. It hit him hard. And he’d say, “Mom, come rub my head.” He wanted to be comforted.

He was so warm and accommodating, such a good son. A good human.

As a child

Brennan was a skateboarder at age 9. We lived in Key Biscayne, Fla., then. He was a beach person at a young age, too. He loved to snorkel.

He was always very out in the world, very self-possessed. Once, when he was about 11, he was in Miami with his dad, and he passed this Cuban fisherman at the waterfront using a simple drop line to fish. Brennan had a really nice fishing pole and he said, “Hey, can we trade?” He actually gave that guy his pole. He was just like that.

What Brennan was proud of

Snowboarding. He traveled to Bariloche in Argentina when he was young — he had a friend from a South American family who brought him. He learned snowboarding there.

I think it made him feel accomplished. He was a natural boarder and athlete. It was his passion, his love. He wasn’t competitive; he didn’t need the accolades, but he could ride with the best of them.

We moved to Vermont for his snowboarding when he was 14. At first Brennan was concerned about the lack of diversity in Vermont. He complained that “You know, it’s only 2 percent racially diverse there.” But he loved it. He snowboarded at Smugglers’ Notch and Stowe.

We wanted to go somewhere safe, away from the drug culture in Florida. As it turned out, we went to a state that was one of the hardest hit by the opioid crisis.

When I first knew something was wrong

Brennan suffered a snowboarding injury, an ACL tear, while in his first year at Sierra Nevada College in Lake Tahoe. He came home from college to recover, and the doctors prescribed an opiate, Dilaudid, for his pain. It turned into full-blown addiction. He eventually moved on to OxyContin, which was all over the streets at the time.

I could see that he was addicted. He wasn’t himself. I called him out, and he denied it. We fought about it for four months.

Finally, he came to me at my acupuncture office — at 19 years old — telling me he wanted to go to rehab. I think about the maturation it took for him to do that and the absolute horror of opiate addiction.

He went to rehab after that, and it took for a little while. But OxyContin grabbed him and held him for seven years.

How opioid-use disorder changed his life

Brennan struggled and suffered like no young man should. He was a victim of the opioid epidemic, which is taking our kids from us like something out of a science-fiction film. They are just disappearing right before our eyes.

How opioid-use disorder changed our relationship

Brennan and I fought about his drug use, because I thought I had control and could fix him. I couldn’t. No one could possibly fix anything as big as this problem — pharmaceutical companies were dumping thousands upon thousands of OxyContin pills into Burlington, Vt., and around the nation in the early 2000s.

An amazing recovery

Brennan had another snowboarding accident in Lake Tahoe in 2012. He was doing a 20-foot jump and fell and hit his head on a rock and suffered a traumatic brain injury. The doctors said it was one of the worst they’d seen. His brain swelled so much he had part of his skull removed and later put back on. He was in a coma for a few weeks. He lost all of his hearing in his left ear.

He came home to recover and had to learn to walk and speak again through months and months of speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy. He worked hard. His father, Robert, and I — and his siblings Colin and Caitlin — helped with his appointments and supported him. We did it together.

He had about five months of clean living after. But he had friends here who were using. I watched him relapse.

The last moment I shared with Brennan

We lost Brennan to an overdose in 2013 in Portland, Maine, while he was in a sober-living situation there. Before he died, he had come to Vermont to see us and get some paperwork sorted out. I brought him to the bus stop up at the University of Vermont, by the Royall Tyler Theatre. We hugged and said goodbye. I was able to rub his head and tell him how much I loved him.

How Brennan would want to be remembered

Brennan would want to be remembered as someone who took each person he came across seriously. He offered them his authenticity, and they were lucky to have it.

If I could say one thing to Brennan now, it would be this

You have so much to be proud of in everything that you are.

Brennan was featured in Mountain magazine’s award-winning 2014 article, “The Spike in Our Veins.”

Margery Keasler leads the Burlington chapter of the support group Grief Recovery After a Substance Passing (GRASP).

We loved Brennan. He was a dear friend of our son, and our family. He had a sweet and unusual open nature. He wore his heart on the outside. We miss him too.

April you guys were his other family.

Brennan was and always will be my best friend. He’d often say to me, “I know you better than you know yourself”. I believe that was true. He was the most emotionally perceptive guy I’ve ever met; truly cared about people and was always so in tune with how everyone was feeling. I know now that Brennan was what is referred to as HSP (highly sensitive person). He used that ability to help people in a profound, but sort of intangible way, that changed the world around him for the better. There are many good people in the world who want to help others situationally. Brennan simply made others feel better, always.

Brennan grew up in a household filled with love and support, which is why I believe he was so outwardly positive, vulnerable, and compassionate with people.

For anyone who was close with Brennan, he was the one who you’d want to talk to about ANYTHING. If it were something excited, he’d share that excitement and glory like no one else. If it were something challenging, scary or painful; he’d make you KNOW that you were strong, capable and already on the path to greatness.

His laugh was contagious. I miss his goofy smile. In the years we spent living and super-fun-having together… my adventures were more fun, drama more entertaining, my soul more understood, and my chest more sore from laughing so hard and so often. Thank you Brennan for making me believe I can live this ridiculous life in any way I dream

Sean,

That is such a beautiful testament to Brennan and our family thanks you for all the love and support you have shown us. Thank you so much for writing those really really beautiful thoughts. They will remain with me forever.